Archive for March 2014

I’ve been reading a bunch of other people’s blogs tonight, and an excellent one, charliejane, has a wide range of subjects that thoroughly discussed all things science fiction, with a slant towards readers and writers of sci-fi. Many participants eagerly join in on all the topics presented, and I even learned a thing or two.

One thing I did notice on the site was the very real question of science behind science fiction. One person who was engaged in a conversation said, “It drives me insane when someone writing space opera gets physics all wrong. It drives me nuts when authors of stories that feature computer hacking don’t know anything about hacking or programming.” That’s a valid point. However, if we’re talking about the future, it’s guaranteed that what exists today regarding hacking and programming isn’t going to be around 40, 60, 80 or 100 years from now.

Jeez, I clearly remember IBM’s cards and the exciting career one could have being a keypunch operator. In 1984, at my first real job that didn’t involve flipping hamburgers, I used an IBM PC jr., which is laughable by today’s standards. I had an “A” drive and a “B” drive, both requiring floppy 5 1/4″ disks. In order to print sideways, I had to put in a separate floppy just for that. And oh, how jealous I was of the resident programmer who had an IBM AT that had – get this – 20K of memory on the hard drive. 20K!

Then, I got a new job in advertising. The agency’s client, among others, was IBM. Since there’s IBM offices worldwide, we needed a way to contact them that didn’t involve staying up all night to make a phone call for a yes or no question. So we had this nifty solution called PROFS. Again, we had a special disk we put in that connected us to the phone line, and we typed up a message that was whisked off to Japan, Australia, Europe – anywhere IBM was located. Several times a day, we’d go and have us a look and retrieve messages. Generally, they’d come the next day, so there was always something in the loop.

You know what they call that technology today? Email. You know what year that was? 1988.

How many of you remember that magical day when the freshly-titled IT guy hooked up a phone line to the back of your computer and you were instantly introduced to the great world beyond your desk? It was 1994 for me, and we had the Internet installed. I had email, too. Netscape was our browser, and we used Webcrawler, Alta Vista and Yahoo! too. There was this button on Yahoo! that said, “Surprise.” One click would take a surfer on a fascinating ride around the internet. I saw plans for plumbing the bathroom, horoscopes, blueberry pie recipes, and all sorts of nifty stuff.

Right along with all of this, there were the evil hackers who learned to take from what the Internet had provided, only to steal and corrupt whatever they could coax their keyboards to type. I dated someone who knew how to do this and back then, it didn’t take much. Today, there’s little that smart kid can’t figure out how to break into.

But in the future?

We know how programming works today and most likely can predict how it’s heading. But there are things we don’t know. My only experience with e-books was watching characters on “Star Trek: Deep Space Nine” read from them. I didn’t know about iPads then. All right, not the best example, but still.

All I’m saying is, true, it’s not a good idea to write about programming and hacking if you don’t know what it is now. But if I lived in 2080, who’s to say what will be the shape of code to come?

Ideas?

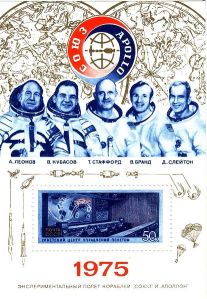

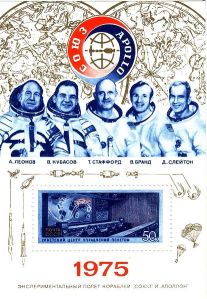

Apollo-Soyuz Crew, as shown on NASA web site, Apollo-Soyuz mission information page

Despite the fact that there always seems to be saber-rattling between the United States and Russia, our space programs get along famously.

Case in point: on July 17, 1975, Soviet and American spaceships linked together for the first time during the mission known as the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project. Three American astronauts, Brig. Gen. Thomas P. Stafford, Deke Slayton and Vance D. Brand and two cosmonauts, Lt. Col. Aleksei A. Leonov and Valery N. Kubasov, changed the way our nations do business in space forever. Slayton, by the way, was one of the original Mercury Seven astronauts

During this nine-day space mission, the American Apollo command/service module, or CSM, linked with a Soviet Soyuz spacecraft. The docking collar, which enabled the two spacecraft to connect, was developed cooperatively between NASA and the Soviet Academy of Sciences. On July 15, 1975, the Soviet Soyuz-U and Delta IB launch vehicles (that’s rockets to you and me) lifted off within seven and one-half hours of each other and docked two days later. After three hours of docking, the hatches opened. Mission Commanders Stafford and Leonov reached towards one another and engaged in the first international handshake in space.

NASA, First international handshake in space: Stafford in foreground, Leonov in background

The joint crew spent 44 hours together conducting scientific experiments, exchanging gifts and flags, visited each other’s ships, ate together and shared a few laughs. Stafford tended to speak Russian with a drawl, prompting Leonov to joke that he spoke “Oklahomski.” President Gerald Ford made a phone call to congratulate the men on their mission, and a statement was read by Soviet President Leonid Brezhnev.

After the mission had ended and both crews returned to Earth, citizens of both nations delighted in shared accomplishment. President Ford personally greeted the cosmonauts. The Americans took their Soviet colleagues and friends on a tour of the United States, and the Soviets returned the gesture with a tour of their own.

In 1977, Soviet astronomer Nikolai S. Chernykh discovered a minor planet in the asteroid belt and named it 2228 Soyuz-Apollo, to commemorate this unique mission.

On February 19, 2014, Valery Kubasov died at the age of 79. No cause was given, but certainly members of the space community of all nations felt the loss of this pioneer of cooperative international missions. He served as the flight engineer and technical expert.

Today, this legacy continues on through the International Space Station and other missions, both off-world and on, through the dedicated scientists, space engineers and others, who recognize that the shared accomplishments and discoveries through cooperation far outweigh those of less peaceful purposes. Perhaps one day scientists will become presidents, and the world will be ruled by logic instead of vice.

One can only hope.

Felis, as depicted in “Uranographia,” Johann Bode, 1801

There are eighty-eight recognized constellations in the evening sky. Depending upon one’s latitude, each will make a grand entrance or hide in the wings. For example, the Southern Cross isn’t visible north of latitude 20 degrees north. Everyone below that enjoys it at least part of the year. Orion hunts nearly all latitudes every winter, but he’ll never catch the little bear in New Zealand. That one never strays that far south, and anyone south of latitude 10 degrees south never will.

Casual stargazers, no matter where on earth they live, will never experience the joys of standing in a dark field to pick out the stars of Felis. And try as one might, The Battery of Volta just won’t appear (although it sounds as if it’d make a great mystery). Sadly, at Christmas, there are no word to express how disappointed a child might be to learn that Tarandus gel Rangifer has better things to do than show up in her backyard.

Why?

Welcome to the world of obsolete constellations.

Yes, folks, if you thought the stars were permanent, well, they are, but it’s their groupings and names that pass on into the literal unknown. They fade into obscurity as we surely all will.

But who gets to name them in the first place? Excellent question. I’ll address that in another blog.

To answer this question on how it applies to constellations, here’s a quick answer: some astronomer made them up. In the case of Tarandus gel Rangifer, it was the creation of French astronomer Pierre Charles Le Monnier in 1736. He wished to commemorate an expedition from Maupertius to Lapland whose goal was to prove the Earth’s oblateness. Rangifer never caught the public’s imagination, or, it would seem, awareness.

Oh, by the way, it means “Reindeer.”

Argo Navis, or the ship Argo, falls into a grey area. It still sails the southern skies (albeit backwards) mainly in the first half of the year, but due to its unwieldy size, it was broken up into four constellations: Carina (keel), Puppis (stern), Vela (sails) and Pyxis (compass). Out of the forty-eight constellations that Ptolemy recognized, it is the only one no longer recognized from that group. You can thank another French astronomer, Nicolas Louis de Lacaille for busting up the ship, as he did in 1752.

One can, however, still piece Argo together, if one chooses. A star grouping shared between Vela and Puppis forms the asterism “False Cross,” which is a poor man’s version of the Southern Cross. So you know, an asterism is a grouping of stars that isn’t officially recognized as a constellation at all. They’re just part of someone else’s turf, like the Big Dipper is really part of Ursa Major.

Next time you stand out on your lawn and give those nightly lanterns a good look and find yourself thinking, “Hmm, who did you used to be?” It won’t be some faded Hollywood has-been…just a few misplaced, rearranged constellations, faded from the celestial scene.

It’s well known that in space, it’s quiet. No noise, no nothing. After all, it’s a vacuum, right?

Truth be told, there is sounds that can be heard, if you know how to listen. Thanks to NASA, they’ve shared terrific examples on their website. Here’s a brief sampling of what lie out there. Let’s start out and work our way in.

But first, a bit of an explanation. Some of these sounds were originally captured as radio waves and were converted into sound. What’s the difference? A sound wave is a longitudinal wave caused by particles passing on vibration. The radio wave is a transverse wave and is electromagnetic waves. In other words, sounds result from causing something to vibrate, whereas radio waves rely on electromagnetic origins.

Returning to our sounds…

In September 2013, Voyager project scientists released to the public sound captured on its durable (or should I say, ‘endurable’?) 8-track tape player. The high-pitched sounds provided evidence that Voyager had entered a region of cold, dense, interstellar plasma. Our worlds-weary intrepid friend had finally left our solar system for good, to seek out whatever lie ahead and dutifully report back its findings. Ready to give yourself the chills? Play this link: Voyager Reports Back.

As Cassini wended its way around Jupiter in 2001, it picked up some interesting radio waves. These are the results of scientists converting the radio to sound waves.

Galileo picked up these transmissions from Jupiter’s largest moon, Ganymede (the first 20 seconds are silent).

Here’s one from Earth. It’s the whistle heard when ultra-cold liquid helium-3 changes volume relative to the North Pole and Earth’s rotation.

And right here on our home planet, directly from the forest, are translated sounds from tree rings. No, it’s not space, but it’s kind of weird.

Enjoy!